There’s always an inherent problem with fancying oneself a charming rogue, and it is that being a rogue isn’t the hard part. Which leads us to Pete Rose and the HBO documentary examining his life, both backward and forward, as he leans into what might be his last play to get into baseball’s Hall of Fame. Charlie Hustle & The Matter of Pete Rose is a thorough and even-handed analysis of a man who cannot help but be simultaneously the hero and victim of his own stories. And finding the charm in that is a search that director Mark Monroe either couldn’t manage or, more likely, didn’t want to.

Up front, Rose was banned from baseball and the Hall of Fame for gambling on his own team as the manager of the Cincinnati Reds. More to the point, though, he remains banned because of the enemies he made, and keeps making. His inability/refusal to take the knee then and now leaves him a tragic, comic, and sometimes even weak figure wrapped in self-absorbed bravado. But charming? Not really, and certainly not here.

Therein lies the real story of Pete Rose. HBO manages the gift of showing highlights of 60-year-old baseball games, the time-machine stuff that sells every sports documentary. There he ladles on his version of charm in that face-first way of his, using his fiendish competitive streak as his personality. And frankly, it works. He isn’t a sympathetic figure as much as an indomitable one, and it is a quirk of the American psyche that we are willing to forgive all of it for someone that outwardly crazed.

But then the story loses itself—because Rose continues to be the one telling it. He could make a compelling case for baseball’s newfound love of gambling and how it holds him in the hypocritical grip of grudge-holding, but that would convince none of the people maintaining his ban. The Hall of Fame has always been a compromised concept. But Rose can’t help himself. Indeed, the closest he comes to getting the depth and breadth of his conundrum is when he says, “Jesse James was a nice guy away from the banks.” Evidently it was the banks’ fault for keeping money around.

None of that is the documentary’s fault. It tells the story as it presents itself, including the charge that Rose had sex with a girl under the age of consent. But it still circles back to Rose because Rose is the reason we are bothering with it at all. That’s where the flaw rests. Rose as the subject means taking Rose as he is, and the view from there is uncomfortable because Rose himself is a hard watch. The things that made him seemingly irresistible as a baseball figure are obstructed by the things that he makes his signature now.

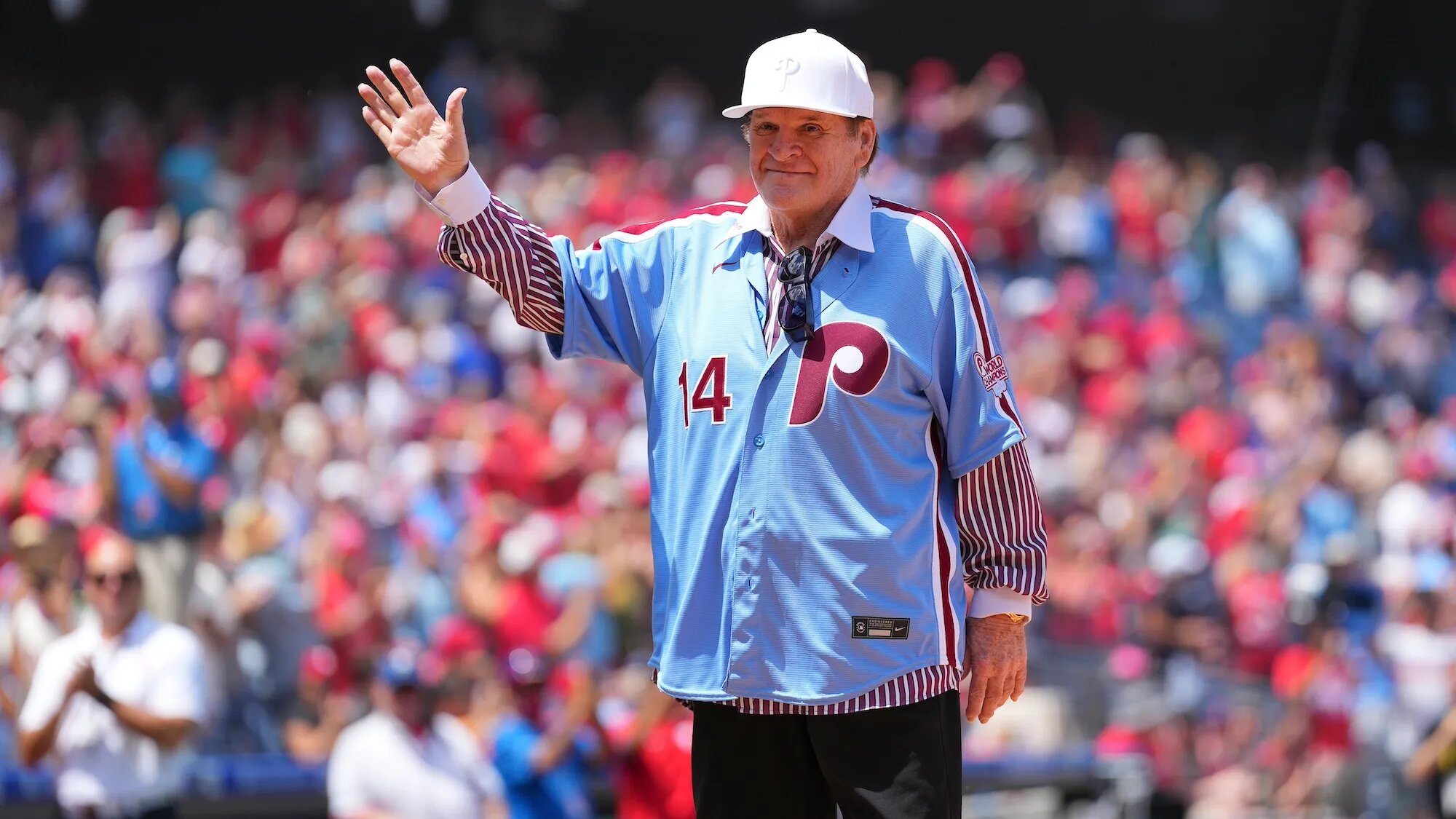

This will almost certainly be the last in-depth view of Rose anyone decides to tackle. He is 83 years old, and his story has largely been the same one since the day he admitted to betting on games. When a Phillies PR person whispers to him—twice—in the tunnel before the team’s celebration, “Do not talk to any reporters,” the juxtaposition between that and the hours HBO lavished on the project letting him explain himself in his own terms is most stark.

In a crusade he must have thought would hinge on his ability to charm a room, he just can’t bring himself to do it, just as he needed someone else to apologize to Philadelphia Inquirer reporter Alex Coffey for him after he called her “babe”—all while he was sitting three feet away because he wouldn’t, or couldn’t, do it himself. When the subject of commissioner Bart Giamatti’s fatal heart attack eight days after Giamatti banned Rose was raised, he denied the unprovable claim that the stress of the investigation caused his death but couldn’t help but say, “Hey, he’s the one who started the investigation.”

When teammate Mike Schmidt says, “He’s so much of an in-your-face guy, it’s unbelievable,” he’s telling you the entire concept of the Rose documentary. Rose made himself the hero of his story until he needed to make himself the victim of his story, and now he’s taken a position he chooses not to escape. He defies you to take a side either way.